The Hindu Right in the United States

Audrey Truschke

Published in the Oxford Research Encyclopedia of American History in October 2022

Abstract — The Hindu Right is a dense network of organizations across the globe that promote Hindutva or Hindu nationalism, a political ideology that advocates for an ethnonationalist Hindu identity and to transform India into a Hindu state governed by majoritarian norms. Hindutva ideology was first articulated in India in the 1920s, and Hindu Right groups began expanding overseas in the 1940s, coming to the United States in 1970. Collectively, the Hindu Right groups that stretch across dozens of nations in the 21st century are known as the Sangh Parivar (the family of Hindutva organizations). From within the United States, Hindu Right groups exercise power within the global Hindutva movement and place pressure on American institutions and liberal values. The major interlinked Hindu Right groups in America focus on a variety of areas, especially politics, religion, outreach, and fundraising. Among other things, they attempt to control educational materials, influence policy makers, defend caste privilege, and whitewash Hindutva violence, a critical tool for many who espouse this exclusive political ideology. The U.S.-based Hindu Right is properly understood within both a transnational context of the global Sangh Parivar and as part of the American landscape, a fertile home for more than fifty years.

Keywords — diaspora, ethnonationalism, Hindu, Hindutva, Hindu nationalism, militancy, right-wing, RSS, Sangh Parivar, violence

———

In September 2019, Indian prime minister Narendra Modi strode, hand in hand, with U.S. president Donald Trump, into a sports stadium in Texas, and a crowd of fifty thousand Indian Americans went wild. The “Howdy Modi” rally drew an enthusiastic audience who waved Indian flags, wore masks of Modi’s face, and even donned saffron cowboy hats.[1] It was a stunning reversal of Modi’s fortunes in the United States, from which he had been barred entry until a mere five years earlier due to his role overseeing mass violence in Gujarat in 2002. In 2019, Modi not only stood on U.S. soil but, moreover, was welcomed by the U.S. president, who provided a warm opening act. The spectacle constituted a key moment that marked the recognition and power accrued by the global ethnonationalist movement of Hindutva—including its acts of violence—that Modi represents.

In his remarks to the Texas crowd, Modi underscored the transnational nature of Hindutva or Hindu nationalism—the political ideology of Hindu supremacy advanced by the Hindu Right. He even referred to his American fans as “my family.”[2] Indeed, the Hindu Right often imagines itself as a family (parivar in Hindi) of organizations who seek to reframe Hindu identity and transform India into an ethnonationalist state. In the 21st century, Hindutva advocates have made substantial progress toward these goals. Under Modi’s leadership since 2014, India has morphed from the world’s largest democracy into the world’s second-largest authoritarian state. Human rights abuses have climbed precipitously as Hindu nationalists forcibly mold India into a Hindu majoritarian homeland.[3] As Hindutva reshapes India and exerts significant effects within diasporic communities (including among those who do not sympathize with all aspects of Hindutva ideology), it is critical to catalog and analyze the U.S. groups who are part of this transnational phenomenon.[4] Hindu Right organizations have found a fertile home on U.S. soil for more than fifty years. This article traces their major structures, networks, key agenda items, and influences. It argues that the U.S.-based Hindu Right groups exert significant power within the global Hindutva movement and place increasing pressure on liberal values and institutions in the United States.

Brief History of Hindutva

The political ideology of Hindutva was initially articulated in India in the 1920s through two key events. First, in 1923, the atheist VD Savarkar published a book titled Essentials of Hindutva, proposing that Hindus embrace an ethnonationalist identity centered on a shared nation, racial heritage, and civilization.[5] Savarkar asserted that only Hindus—in his newly defined sense—could be truly Indian. He demonized Muslims, projecting them as a common enemy of all Hindus, and advanced a mythology of ancient India featuring Hindu heroes and Muslim despots. Savarkar also endorsed violence as a key facet of Hindu identity, a central feature in Hindutva’s second early defining moment, namely, the formation of a paramilitary Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS) in 1925.[6]

The all-male RSS organizes itself into local shakhas (branches) that gather groups of Indian men, often daily, for arms training and ideological indoctrination in Hindutva. Its most famous contribution to history is that an RSS man assassinated the great independence leader Mahatma Gandhi in 1948, which prompted the first (but not the last) temporary Indian ban on the RSS.[7] In 2022, nearly a century after its beginning, the paramilitary RSS—known overseas as the Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS)—serves as the central organization within the array of global groups known collectively as the Sangh Parivar (family of the RSS) or the Hindu Right. Scholars see little change in the basic contours of Hindutva over the past century, except that this ideology—once considered a fringe extreme—has gained astonishing popularity and influence in recent decades.[8]

After India gained independence from the British in 1947, the RSS and other Hindu Right groups began to expand overseas, coming to America after the 1965 Immigration Act opened the doors to skilled migrants from South Asia.[9] Many Indian immigrants to the United States do not affiliate with the Hindu Right. But those who do continue to promote the same basic Hindutva ideology articulated by Savarkar, including collapsing Indian and Hindu identities, maligning Muslims, embracing aggression and violence, and advancing propaganda about Indian history. U.S.-based Hindu Right groups also intersect with other conservative and hateful ideas, including those sourced from South Asia (e.g., casteism), those sourced from America (e.g., white supremacy), and those shared by the two (e.g., patriarchy). Many scholars have sought answers for why some Indian Americans choose to support Hindutva, often using Benedict Anderson’s framework of “long-distance nationalism,” in which a group identifies with an ancestral homeland.[10] Certain aspects of American society may also play a role, such as the American version of multiculturalism that can inspire expressions of an exclusive ethnic identity.[11] Undergirding both processes in the case of Hindutva is the Sangh Parivar, a collection of Hindu Right groups—first formed in India and then replicated in countries across the world, including in the United States—that promote Hindu supremacy. Hindu Right groups are highly organized and have made robust, multipronged recruitment efforts to woo sections of the Indian American diaspora.

Global Sangh Parivar

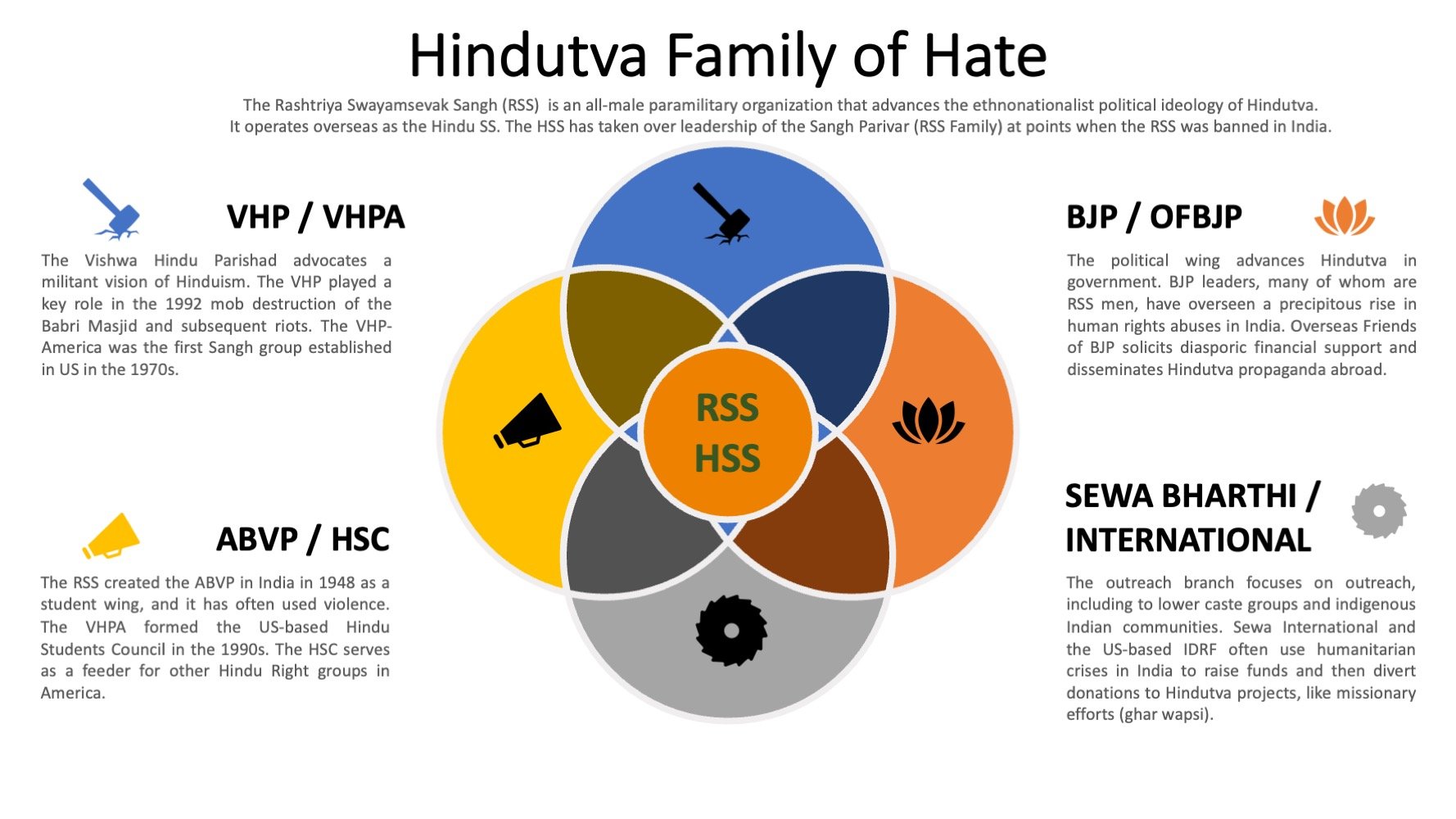

The Sangh Parivar—the coalition of groups that propagate Hindutva—are centered on the RSS. As mentioned, the RSS is paramilitary, and its staple activities include weapons training and ideological instruction for men (women are barred from being members).[12] The RSS sets the general agenda for the rest of the Hindu Right, often disseminating broad goals and strategies. Other large groups lead discrete wings of the Indian Hindu Right focused on specific social areas, including student affairs (Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad [ABVP]), religious concerns (Vishwa Hindu Parishad [VHP]), outreach (Sewa Bharthi), and politics (Bharatiya Janata Party [BJP]). Within each wing, the major organizing group oversees many smaller organizations with even more specific foci. The diffuse nature of the Sangh Parivar is part of its brilliance. Many organizations act—each in their own ways—in pursuit of a centrally articulated set of goals. At once, the Hindu Right is both highly organized and—outside of its major organizing groups—almost impossible to exhaustively describe or catalog.

The Sangh Parivar began to establish Hindu Right groups outside of India in 1947, the year of Indian independence. Hindu Right leaders since have viewed diasporic Indians as useful in the Hindu nationalist cause and obligated to promote it. MS Golwalkar, the second head of the RSS and the Sangh’s “ideological architect” described how a Hindu who leaves India “will go out as a representative of the country, the national culture and values of life—which have given birth to him.”[13] In this Hindutva view, nationalist burdens weigh on all Indians, even those who migrate elsewhere. The Sangh Parivar propagated this notion by replicating its India-based groups in other nations, thus making Hindutva a global movement.[14] All the overarching India-based Hindu Right groups have sister or parallel organizations—often with similar names—in the United States, as charted in Figure 1 (“The Global Sangh Parivar”).

Hindu Right groups operate freely in America, although some of their sister organizations in India—most notably the VHP—have been flagged as militant by the CIA.[15] Given this, some U.S.-based Hindu Right groups attempt to paper over, or even flatly deny, their connections with India-based groups, including parent organizations.[16] But this is nothing more than a facile ploy. Sangh Parivar groups are connected across national borders through a dense web of overlapping individuals, hierarchies, shared histories, and, above all, their commitment to the ideology of Hindutva.

Vishwa Hindu Parishad and Hindu Militancy

The VHPA—the American version of the VHP that articulates a homogenous, militant version of Hinduism—was established by four RSS members in 1970 and formally incorporated in numerous American states in 1974.[17] It is more common for the RSS to be the first Sangh group in a country (usually titled as the HSS). That the VHP came first to U.S. shores is perhaps a nod to American religiosity and the great leeway generally afforded to groups who claim to be promoting religious ideas. Additionally, Hindu spiritual teachers have mesmerized North American audiences since the late 19th century, and that history may have made the United States especially ripe for a VHP presence.[18] Indeed, in 1973, the RSS head MS Golwalkar wrote a letter urging a young RSS émigré to Canada to cultivate and capitalize on acquaintances with Hindu holy men.[19]

The VHPA follows its Indian parent group in encouraging militant, including violent, behavior among Hindus. For instance, The VHPA provided support during the aftermath of the Indian VHP’s successful movement to illegally demolish the Babri Masjid, a premodern mosque in Ayodhya, a north Indian city. In a spectacular display of muscular Hinduism, a Hindu mob tore down the Babri Masjid, brick by brick, on December 6, 1992, which unleashed mass violence against Muslim communities that killed several thousand in North and Central India. The VHP was temporarily banned in India for its pivotal role in these horrors, and so in 1993, the VHPA hosted a conference that platformed Indian VHP leaders.[20] At the event, Uma Bharati, a key agitator in the 1992 mosque destruction, used her American stage to denounce Hindus who did not support militancy, yelling at a nonviolent crowd in Washington, D.C.: “To those of you who say you are ashamed to be Hindus, we want to tell you: we are ashamed of you. After December 6, the tiger has been let out of the cage.’”[21] A year later, in 1994, the president of the VHPA, Yash Pal, made a speech commemorating Hindu militants who had been killed in 1990 and called for the diaspora to support the BJP.[22] Building on this transnational embrace of militancy, in 1998 the VHPA issued a ten-point code of conduct for Hindus, including encouraging “assertiveness and aggressiveness.”[23] Even in the 2020s, a common talking point among the Hindu Right is that Hindus are too peaceful and should become more bellicose in order to advance their ideas.

The VHPA established other groups to disseminate Hindu Right propaganda, most notably the Hindu Mandir Executives’ Conference (HMEC) in 2006. HMEC works with Hindu temples and the online magazine Hinduism Today to promote Hindutva literature and disinformation, especially targeting second-generation Indian Americans. The VHPA itself has continued to platform militants and hate mongers in recent years. For instance, in April 2021 the VHPA planned to host Narsinghanand Saraswati, a well-known Hindutva advocate in India who has openly called for a genocide of Indian Muslims on several occasions.[24] Under outcry from other Indian diaspora groups, the VHPA canceled the lecture. But the VHPA proceeded with another event in Washington, D.C., in the summer of 2021, that platformed both an Islamophobic propagandist and a participant in the January 6, 2021, attempted insurrection in the United States.[25] As discussed in the section “Intersectional Right-Wing Hate,” Hindutva intersects with numerous other hateful ideologies and alt-right movements in the U.S. context.

Rashtriya/Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh and Online Hindutva

The HSS—the RSS overseas—was founded in the United States in 1989. The HSS was established decades earlier in other nations, such as the United Kingdom where it was founded in 1966. The slight name change replaced “Rashtriya” (national) with “Hindu,” both because “national” made less sense outside of India and as a sign of the Sangh Parivar’s ambitions of becoming a global movement. The HSS took on new importance between 1975 and 1977 when the RSS was banned in India, and so the HSS took over the mantle of leadership for the Sangh Parivar.[26] Overall, the HSS replicates the RSS structure, organizing itself into shakhas (branches) with hundreds scattered across the United States as of 2022.[27] When the HSS first established itself in the United States, it sought to attract members from a diaspora that, due to U.S. immigration policies, is highly educated and wealthy.[28] This required adjusting the nature of shakha activities. As Christophe Jaffrelot and Ingrid Therwath have put it, “There was no way that business executives, the prime HSS target, were going to get up at dawn to salute the saffron flag reciting a Sanskrit anthem—and even less do calisthenics in khaki shorts!”[29] One solution was to establish cyber-shakhas.

The Hindu Right was an early adopter of the internet for organizing and disseminating their ideas, and U.S.-based groups have often led Hindutva’s internet presence. For instance, in the late 1990s, the Hindu Students Council (a VHPA project) launched the Global Hindu Electronic Network (GHEN) to promote Hindutva ideology. Numerous other Hindu Right websites followed, along with message boards, email lists, and the like. Online organization made good sense given the transnational nature of the Hindutva movement. It also had the added benefit of enabling territorial claims about India to be advanced from overseas. As one researcher has put it, “Online hindutva is thus very territorialized and symbolically linked to India, while operating from the United States.”[30] Building upon the U.S.-based Hindu Right’s early embrace of the internet, India’s Hindu nationalist leaders in the 21st century often rely on groups organized online, including WhatsApp groups to share propaganda and a troll army to attack dissenters.

Overseas Friends of Bharatiya Janata Party, Outreach Branch, and Financial Support

Political diaspora groups such as the Overseas Friends of BJP support India’s major Hindu nationalist political party, the BJP, ideologically and financially. Like other US-based Hindu Right groups, Overseas Friends of BJP (OFBJP) began as an outreach project of members of India-based Sangh Parivar groups. Specifically, Lal Krishna Advani, one of the BJP’s co-founders and an RSS man, founded OFBJP in 1992. His goal was to do “damage control” surrounding the 1992 Babri Masjid destruction and to solicit financial contributions from a wealthy diaspora.[31] After Modi became India’s prime minister in 2014, the BJP decided to expand its overseas branches, and in the fall of 2014, Modi personally met with members of the U.S.-based OFBJP in New York.[32] The U.S.-based OFBJP has lived up to its propaganda and financing expectations. For instance, it helped to organize the “Howdy Modi” spectacle of 2019. On the softer side of Hindutva, OFBJP promotes International Yoga Day, a Modi initiative that collapses Indian and Hindu identities. As of 2020, OFBJP is formally registered as a foreign agent in the United States, acting on behalf of India’s BJP.[33]

The Sangh Parivar has an active outreach wing, and the two largest groups in the United States are the India Development and Relief Fund (IDRF) and Sewa International, the latter an offshoot of the HSS. In imitation of their Indian counterpart, Sewa Bharthi, both IDRF and Sewa International advertise themselves as social service organizations that provide for the poor and alleviate human suffering. But they serve broad Hindutva purposes. Specifically, both groups divert some of the money that they fundraise by pulling on peoples’ heart strings toward Hindutva activities, such as missionary outreach to indigenous groups in India and violence against Muslims.[34] Both the IDRF and Sewa International have been subjects of exposés centered on their misuse of American—or, in Sewa International’s case, United Kingdom—funds to the tune of millions of dollars each.[35] A report on the IDRF in 2002 was damning enough to convince large U.S. corporations to halt matching contributions to the group.[36]

Additional outreach groups have also come into focus for their role in directing US money to Hindutva causes in India. For example, the Param Shakti Peeth (PSP) of America funds a program established by the VHP in India. PSP has collected millions in US donations, including from Sangh-affiliated family foundations in the United States.[37] Patanjali Yogpeeth-US (PYP-US or PYP Yog) is headed by well-known figures in the American Sangh, including members of the Aggarwal, Bhutada, and Malani families (who have played key roles in the VHPA, HSS, OFBJP, Hindu American Foundation, Ekal Vidyalaya, and other groups).[38] PYP Yog claims to promote yoga, but two things suggest otherwise. The group has links to an organization in India headed by Baba Ramdev, a billionaire widely known to have supported Modi’s rise to power.[39] Also, PYP Yog has sent significant money to India for “disaster relief,” a departure from its mission that has led to calls for further investigation of possible “financial and administrative irregularities.”[40]

Cultivating Hindu Right Leaders on Campus

At present, two major Hindu Right student groups operate in the United States, each with dozens of chapters on discrete campuses: the Hindu Students Council (a VHPA project, founded in 1987) and the Hindu Youth for Unity, Virtues and Action (YUVA, a HSS project, founded in 2007). The Sangh Parivar has long perceived college campuses as a key arena for promoting Hindutva. The ABVP—the sister Hindu Right student organization in India—was one of the earliest offshoot groups established by the RSS in 1948.[41] In India, ABVP members are frequently violent, and, accordingly, they have often met with resistance in direct outreach efforts to the United States, such as at Georgetown in 2019.[42] The Hindu Students Council (HSC) and Hindu YUVA are better positioned to achieve the layered goals of the Hindu Right on American college campuses. Both groups advocate basic Hindutva ideas, especially concerning Hindu identity in what is sometimes described as soft Hindutva. As Vijay Prashad has put it, the HSC promotes a “syndicated Brahmanical Hinduism” that is interlaced with casteism, patriarchy, and intolerance for other religious traditions.[43] Exposure to such ideas helps to normalize Hindu Right propaganda within the Indian diaspora, even among those who might not identify with Hindutva ideology. That said, some chapters of these student groups have experienced internal dissent, especially concerning misogyny and hate speech against Muslims.[44]

In addition to its broader outreach efforts, the HSC also serves as a feeder group, cultivating the next generation of Hindu Right leaders in America. Many former HSC members have leadership roles in other U.S.-based Hindu Right organizations. In some cases, affiliates of the HSC have even gone on to receive training from the RSS in India.[45] A 2008 report, titled “Unmistakably Sangh,” laid bare the extensive links between the HSC and other Sangh Parivar groups. The report also noted that many college students experience a more casual affiliation with the HSC, perhaps celebrating Diwali or Holi with a local chapter and remaining unaware of the group’s extremist links. Part of the strategy of the U.S.-based Hindu Right is making its organizations appear harmless to many in the Indian American community and then using the cover that goodwill provides to advance Hindutva goals. As Vinayak Chaturvedi recently noted, “Nearly every major university in the United States has a student organization connected to the Sangh Parivar,” and these groups play varying roles in Hindutva intimidation, blacklisting, ad hominem attacks and threats, and monitoring of students and professors.[46]

The Sangh’s Web

The Sangh Parivar often operates like a web comprised of a messy crisscrossing pattern of ideological, individual, and financial ties. The Hindu American Foundation (HAF), founded in the United States in 2004, offers a case study in how this dizzying array of links informs the creation of new groups and persists over decades. The HAF’s founders in the early 2000s had well-documented ties to the VHPA, HSS, HSC, BJP, and even the RSS. A particularly eye-popping connection is that Mihir Meghani—one of the HAF’s founders—wrote a manifesto for the BJP in the 1990s titled “Hindutva: The Great Nationalist Ideology” that spoke of a deep well of Hindu anger and praised the destruction of the Babri Masjid. In one crescendo within the piece, Mr. Meghani proclaimed, “Hindutva is here to stay,” and he warned that Muslims must embrace this “new nationalistic spirit of Bharat.”[47] Even the very name of the HAF—which forefronts a religious rather than a regional or cultural identity—bore the strong mark of the VHPA. In the 1990s, the VHPA began to posit the identity of “American Hindus” that, as per Hindutva’s othering tendencies, set Hindus apart from other religious groups in the South Asian diaspora.[48] The Hindu American Foundation is unthinkable, even in name, without the wider Sangh Parivar context.

The HAF’s Sangh ties are as robust in the present as they were at its founding and have helped mold the group’s agenda items for close to two decades. Exposés on the HAF in 2020 and 2022 highlighted the organization’s extensive financial connections with both U.S.-based and India-based Sangh groups.[49] To give one example, HAF’s treasurer, Rishi Bhutada, served as the head spokesman for the 2019 “Howdy Modi” event. Rishi Bhutada also served on the board of the Bhutada Family Foundation, which regularly contributes substantial money to the HSS, the HSC, and the HAF.[50] Sangh Parivar ties are necessary for the HAF to operate within the larger global Hindutva movement. Indeed, the organization has been a leader on the issues of protecting caste privileges and placing pressure on higher education, as discussed in “Core Issues for the American Sangh Parivar.” However, ties with overseas groups can be a liability given the HAF’s focus on whitewashing aspects of Hindutva for a broad U.S. audience. Accordingly, despite extensive evidence to the contrary, the HAF regularly denies its links with other Hindu Right organizations.

The Sangh Parivar comprises many other groups, some conceived on a local level, around caste identities, and/or focused on specific issues. Many Hindu Right groups have more limited resources than the large organizations detailed here. Some additional groups come up in the next section (“Core Issues for the American Sangh Parivar”), which discusses signature U.S. Hindu Right campaigns. But it is worth underscoring that the Sangh Parivar can never be exhaustively described. It is an ever-shifting set of groups, at once highly organized and dispersed. The proliferation of smaller-scale Hindu Right groups—which are often subjected to less scrutiny than more visible organizations—has advantages in the United States context in which Hindutva ideology clashes with widely held social values of inclusion, religious freedom, and human rights.

Core Issues for the American Sangh Parivar

Children’s Programming

The U.S.-based Hindu Right prioritizes several key programs and objectives, beginning with indoctrinating their own children. In part, the focus on child development reflects a broad anxiety of losing second- and third-generation Indian Americans to more general American culture.[51] Both the HSS and the VHPA boast seven-figure annual budgets as of 2019, much of which each group devotes to programming for children, especially weekly Hindutva-aligned religion classes called Bal Vihar (HSS), the youth forum Balagokulam (HSS), and youth summer camps (HSS and VHPA).[52] The summer camps, which have run since the early 1980s, feature some classic RSS activities, such as chanting slogans, conducting military drills, and inculcating hatred of others.[53] A major objective is to form youth into contributing members of Hindu Right groups for life, which sometimes works. For instance, one volunteer wrote appreciatively for Hinduism Today, a magazine that often showcases Hindu Right output, about having volunteered for a VHPA “Hindu Heritage Camp” in 2001 and, as of 2018, was an active VHPA volunteer.[54] Hindu Right groups also run parenting seminars that aim to educate parents in how to talk to their kids about Hinduism, using a definition of the tradition consistent with Hindutva.[55]

Controlling Textbooks and Protecting Caste Privilege

The U.S. Hindu Right also seeks to control what all American children learn about India and Hinduism, as seen in the two California textbook controversies (2005 and 2016–2017). In both cases, Hindu Right groups—including the Vedic Foundation, the Hindu Education Foundation (effectively the HSS), and the HAF—proposed textbook edits designed to whitewash caste and patriarchy in ancient India and within Hinduism.[56] Structurally, the Hindu Right arguments followed closely on the allegations made by white supremacists that teaching about racism will make white kids feel guilty and expose them to bullying. Similarly, Hindu Right groups argued that upper-caste Hindu children would be targeted in any frank discussion of caste. In both California textbook controversies, academics and diverse Indian diasporic coalitions (including many Hindus) opposed the anti-intellectual edits requested by the Hindu Right.

The Hindu Right’s vehemence in the two California textbook controversies is partly explained by the toxic casteism that is endemic to the Hindutva movement. Caste-based discrimination is a pervasive social and civil rights issue in both India and the United States.[57] For instance, in a recent prominent case, a Hindu sect known as Bochasanwasi Akshar Purushottam Swaminarayan Sanstha (BAPS)—which has Sangh Parivar links—was raided by the FBI and accused of using forced Dalit labor across at least five American states. This case has been reported as the largest instance of alleged forced labor on U.S. soil since the 1990s.[58] More broadly, when polled, Indian Americans evince high awareness of caste within their social networks, and Dalits in America report alarming rates of caste-based discrimination.[59] But the Hindu Right strongly prefers to not discuss, much less confront, the problem of caste on two scores. One, the global Hindu Right is invested in projecting unity and homogeneity across Hindu traditions. They fear that recognition of caste-based discrimination will fragment their movement, especially electoral gains in recent years among historically oppressed caste communities in India.[60] Two, Hindutva organizations are often structured by casteism. Many major Sangh Parivar groups, including the RSS, are predominantly run by upper castes, sometimes by Brahmins specifically. This pattern of upper-caste dominance holds within U.S.-based Hindu Right groups as well, which often defend caste privilege.

Attacking Academics

U.S.-based Hindu Right groups target higher education with the goal of exerting ideological control, or at least serious restraints, within the study of India and Hinduism. As mentioned, Hindutva is an anti-intellectual ideology in that it stipulates a certain set of myths about Indian history that cannot be questioned. In contrast, academics question everything within the rubric of intellectual inquiry. A group of academics known as the South Asia Scholar Activist Collective (the author is a member) have collated about two dozen discrete cases of Hindutva harassment of academics in North America, stretching back to the 1990s.[61] In addition to groups mentioned already, the Infinity Foundation run by Rajiv Malhotra is a repeat offender in attempts to curtail scholarly views about Hinduism and South Asian history that do not support Hindu Right ideological commitments. Hindutva harassment in North America most often relies on bad-faith readings of academic work and, especially in recent years, has involved heavy intimidation and violent threats. At times, Hindu Right groups have also tried to flex their muscles by controlling appointments at universities, most publicly through an attempt by the Dharma Civilization Foundation to select for ideology in four chair positions at the University of California–Irvine in 2015.[62] The Uberoi Foundation for Religious Studies is worth mentioning for its recurrent attempts to use financial gifts to American universities to compel positions and even scholarly appointments that are Hindutva-friendly. In 2021, a combination of U.S.-based and India-based Hindutva groups spearheaded the most robust set of assaults on academics witnessed to date, in which numerous threats of violence targeted an academic conference on global Hindutva that was sponsored by dozens of universities.[63] The Hindu Right seeks to control its own image, and so often opposes scholarly attention to Hindutva ideology.

Political Propaganda and Fundraising

The U.S.-based Hindu Right advances propaganda in favor of the BJP, including Prime Minister Narendra Modi, both to the American public and to lawmakers. A tricky issue here is that Modi oversaw the 2002 Gujarat Pogrom, in which thousands of Muslims died and hundreds of thousands were displaced. This act of incredible violence made Modi unpalatable to many overseas, including in the United States where he was denied a visa twice in the decade following the pogrom.[64] As noted, Hindu Right–organized events that celebrated Modi’s return—most recently, the 2019 “Howdy Modi” rally, and before that a gathering that attracted near twenty thousand people at Madison Square Garden in 2014 —issue visible counters to Modi’s earlier status as persona non grata on American soil.[65] Many U.S. Hindu Right groups also engage in lobbying efforts to curate the American view of Modi, the BJP, and Hindu nationalism. Some groups also seek a more direct route of introducing Hindu Right viewpoints to U.S. politics by funding individuals sympathetic to Hindutva to run for political office in the United States.

Fundraising for the Indian Sangh Parivar is a critical goal of the U.S.-based Hindu Right. Indian Americans are among the wealthiest minority group in America, owing to immigration policies that largely restrict immigration from South Asia to skilled migrants. U.S. Hindu Right groups use funds to promote their own efforts, and some also channel money to India to support Sangh activities there. It is difficult to track U.S. money abroad, but both the RSS and the VHP report receiving significant United States dollars as early as the 1990s.[66] As mentioned, the IDRF and other outreach groups have funneled millions into Sangh Parivar groups in India while misleading their U.S. donors. The Ram temple in Ayodhya—being constructed on the spot of the destroyed Babri Masjid as of 2022—has attracted U.S. financial support since the 1990s.[67] Owing to the bad press surrounding these issues and, perhaps, the dark realities of the money trail, U.S. Hindu Right groups are often sensitive to discussions of their finances.

Intersectional Right-Wing Hate

As the Hindu Right has made a home in the United States since 1970, it has found numerous issues on which to dovetail with other American right-wing causes and ideologies. At times, this is a good fit. For instance, the U.S.-based Hindu Right expresses extreme levels of Islamophobia, an ideology especially pronounced throughout American society since the attacks of September 11, 2001. This shared stance has enabled specific Hindu Right groups to pursue relationships with Zionist organizations (despite the documented history of Hindutva admiration for Nazis).[68] Additionally, Hindu Right attacks on the academy have found common ground with other anti-intellectual alt-right movements. For instance, some staff members at the HAF—which prioritized attacks on higher education in 2021—have links with the Koch network, perhaps the most common American source of threats to academic freedom.[69]

The Hindu Right also forges more fraught alliances, such as with white Christian nationalists. For instance, the Coalition of Hindus of North America (CoHNA), a relatively small Hindu Right organization, hosted an event in 2021 featuring congressman Drew Ferguson, a Georgia Republican who openly advocates that the United States was founded on Judeo-Christian principles and sought to overturn the 2020 election results.[70] In 2022, they held a similar event featuring Georgia Republican Andrew Clyde, who espouses similar stances on the non-separation of church and state as well as the 2021 insurrection. The executive director of the Hindu American Foundation also spoke at the 2022 Clyde event.[71] Few Hindu Americans, right-leaning or otherwise, support such views, but the alliance served CoHNA’s narrow interests at that event of alleging American intolerance of right-wing religious groups. On a bigger stage, the 2019 “Howdy Modi” event was attended by Republicans Donald Trump and Ted Cruz, while being shunned by all Indian American lawmakers except for Raja Krishnamoorthi, whose financial links with Hindu nationalist groups are well-established.[72]

Other U.S.-based Hindu Right organizations have found themselves uncomfortably aligned with conservative Christian groups. One example is an endeavor that the HAF launched in 2008: the Take Back Yoga campaign. Yoga is a prime medium through which Hindu Right groups disseminate soft Hindutva ideas (e.g., see discussion under “Overseas Friends of Bharatiya Janata Party, Outreach Branch, and Financial Support”). HAF’s campaign specifically posited that yoga had strong Hindu roots (an idea at odds with the scholarly consensus that yoga is multi-sourced). HAF’s position, later articulated by other Hindu Right groups such as CoHNA, was endorsed by some Christian Right groups, who cited these supposed historical connections with Hinduism to argue that teaching yoga in public schools violates the American Establishment clause. This issue has arisen repeatedly, most recently in Alabama in 2021 when the state legislature lifted a ban on teaching yoga in public school. But, so as to divorce yoga from its religious roots as posited by Hindu and Christian right-wingers, Alabama bars the use of any Sanskrit names for yoga poses.[73]

The U.S.-based Hindu Right adopts white supremacist language at times and even aligns with members of this movement. One area where this comes out is political endorsements.[74] For instance, numerous leaders among the American Hindu Right supported Tulsi Gabbard’s bid for the 2020 Democratic nomination for president.[75] Gabbard was also endorsed by former KKK grand wizard David Duke. Polling indicates that most Hindu Americans vote Democrat, but there is support for Republicans by some within the Hindu Right. For example, during the 2016 presidential campaign, a group formed called “Hindus for Trump,” which even produced a poster featuring Trump as a Hindu deity on a lotus in American patriotic colors (see Figure 2). Commenting on this group, the comedian Jimmy Kimmel remarked, “This is the first time a group of Hindus has ever endorsed a candidate who has his own line of signature steaks.”[76] “Hindus for Trump” is far easier to understand if the group is considered within—if admittedly on the fringes—of the U.S. Hindu Right, complete with the movement’s array of ties with other conservative ideologies. Indeed, “Hindus for Trump” hosted then candidate Donald Trump at a rally in New Jersey in 2016 where “radical Islamic terrorism” was repeated ad nauseum as the glue that bound the candidate to this special interest Hindu Right group.

Conclusion: Resisting the Hindu Right

The U.S. Hindu Right has always had critics, both among those who articulate a different relationship to their heritage and among a diverse set of groups that explicitly seek to counter Hindutva propaganda and harassment. For instance, the Campaign to Stop Funding Hate was formed by a diverse group of Indian Americans after the 2002 Gujarat Pogrom and has since lobbied for inclusive policies as well as produced detailed exposés of Hindu Right organizations in the diaspora.[77] Founded in 2019, Hindus for Human Rights articulates a Hindu American identity that rejects Hindutva ideology. On college campuses, the South Asian Students Association (SASA) has long offered cultural programming that welcomes people from diverse religious and national backgrounds.[78] More recently, Students Against Hindutva Ideology (SAHI) kicked off in 2020 with a campaign they called “Holi Against Hindutva,” building on the longstanding precedent in both the diaspora and India of advancing political commentary through festivals. In 2021, the South Asia Scholar Activist Collective unveiled the Hindutva Harassment Field Manual, an online resource for targets and allies of those attacked by the Hindu Right in North America.

The flurry of more recent opposition to Hindutva in the United States is a proportionate response to the increased power of this ideology in India and its efflorescence in America. Going forward, the topic is likely to attract further attention, from both activists and scholars. As that happens, the operations of the various groups that compose the U.S.-based Hindu Right will be subjected to additional scholarly scrutiny that produces a more nuanced, precise understanding of the American role in the global Hindutva movement.

Primary Sources

Hindu Right groups typically register as nonprofits in the United States, which compels them to make certain financial disclosures. Tax documents, such as 990s, can be useful, often available on GuideStar or ProPublica’s Nonprofit Explorer. Many Hindu Right groups in America have websites, including the following:

Balagokulam, https://balagokulam.hssus.org/

Coalition of Hindus of North America, https://cohna.org/

Dharma Civilization Foundation, https://dcfusa.org/

Ekal Vidyalaya, https://www.ekal.org/us

Hindu American Foundation, http://hinduamerican.org/

Hindu Education Foundation, https://www.hindueducation.org/

Hindu Mandir Executives’ Conference, http://www.hmec.info/

Hindu Students Council, https://www.hindustudentscouncil.org/

Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh (HSS), https://www.hssus.org/

Hindu YUVA, https://hinduyuva.org/

India Development and Relief Fund, https://www.idrf.org/

Infinity Foundation, https://infinityfoundation.com/

Overseas Friends of BJP, http://ofbjp.bjp.org/

Param Shakti Peeth of America, https://pspausa.org/

Patanjali Yogpeeth-US (PYP Yog), https://pyptusa.org/

Sewa International: https://www.sewausa.org/

Uberoi Foundation for Religious Studies, https://www.uberoireligiousstudies.org/

Vishwa Hindu Parishad of America, https://www.vhp-america.org/

United States-based Hindu Right groups were early adopters of the internet, which has left extensive online primary sources. The most far-reaching website was probably the Global Hindu Electronic Network (http://www.hindunet.org) and Sword of Truth the most extreme (http://www.swordoftruth.com). The magazine Hinduism Today (https://www.hinduismtoday.com/) frequently propagates Hindutva ideas and is still published as of the time of writing (January 2022). Some of the early websites are defunct as of 2022 but can be accessed via the Wayback Machine. Sometimes internal listserv messages are available, such as VHPA listserv messages dated between 1996 and 1999 and the BVP listserv (still active as of February 2022). Social media also offers robust primary source materials from Hindu Right groups and individuals.

For Indian perceptions of the US Hindu Right, the RSS’s mouthpiece, Organiser (https://www.organiser.org/) is useful. Swarajya (https://swarajyamag.com/) and OpIndia (https://www.opindia.com/) are two alt-right websites that frequently cover US Hindutva news.

The California textbook battles of 2005 and 2016–17 generated many letters and community input from both sides. The Friends of South Asia—a diverse coalition of Indian Americans and scholars—maintains a list of letters opposed to the Hindu Right’s proposed changes.

Links to Digital Materials

2002 report of misuse of funds by the IDRF, “The Foreign Exchange of Hate: IDRF and the American Founding of Hindutva.”

2004 expose on HSS and Sewa International in the United Kingdom, “In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism.”

Campaign to Stop Funding Hate’s 2008 Report on the Sangh Parivar links of the Hindu Students Council, “Unmistakably Sangh: The National HSC and its Hindutva Agenda.”

Coalition to Stop Genocide’s 2013 Report on the Hindu American Foundation, in 2 parts: (1) “Affiliations of Faith: Hindu American Foundation and the Global Sangh” and (2) Affiliations of Faith: Joined at the hip.”

Sadhana’s 2019 American Hindu perspective on how to confront Hindutva extremism, “Hindutva 101: A Primer.”

2020 scholar’s testimony on “Transnational Hindutva Networks in United States” to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom.

Hindutva Harassment Field Manual, a project of the South Asia Scholar Activist Collective, 2021.

Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021: The Infrastructure of Hindutva Mobilizing of Jasa Macher, May 2022, Released via sacw.net.

Further Reading

Ahmed, Manan, Rohit Chopra, and Audrey Truschke. “North America Has a Hindu Nationalist Problem, and Scholars are On the Frontlines of These Right-Wing Attacks.” Religion Dispatches (October 2021).

Bose, Purnima. “Hindutva Abroad: The California Textbook Controversy.” The Global South 2, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 11–34.

Bridge Initiative Team. Factsheet: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). 2021.

de Souza, Rebecca, and Syed Ali Hussain. “Howdy Modi!”: Mediatization, Hindutva, and Long Distance Ethnonationalism,” Journal of International and Intercultural published online (2021).

Kurien, Prema A. A Place at the Multicultural Table: The Development of an American Hinduism. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007.

Jaffrelot, Christophe, ed. Hindu Nationalism: A Reader. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Jaffrelot, Christophe, and Ingrid Therwath, “The Global Sangh Parivar: A Study of Contemporary International Hinduism.” In Religious Internationals in the Modern World: Globalization and Faith Communities since 1750. Edited by Abigail Green and Vincent Viaene, 343–364. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

Jaffrelot, Christophe, and Ingrid Therwath. “The Sangh Parivar and the Hindu Diaspora in the West: What Kind of ‘Long-Distance Nationalism’?” International Political Sociology 1 (2007): 278–295.

Mathew, Biju, and Vijay Prashad. “The Protean Forms of Yankee Hindutva.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 23, no. 3 (2000): 516–534.

Rajagopal, Arvind. “Hindu Nationalism in the United States: Changing Configurations of Political Practice.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 23 (2000): 467–496.

Rajagopal, Arvind. “Transnational Networks and Hindu Nationalism.” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 29, no. 3 (1997): 45–58.

Glossary and Acronyms

ABVP: Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, within the Sangh’s student wing

Babri Masjid: a premodern mosque built in the early 16th century and destroyed by a Hindu mob in 1992. As of 2022, a Hindu temple is being built on its former site and is a key issue for the global Hindu Right.

BAPS: Hindu denomination

BJP: Bharatiya Janata Party

Caste: discriminatory system of hereditary social hierarchy

CoHNA: Coalition of Hindus of North America

Dalit: caste-oppressed individuals and communities; formerly known as “untouchables”

Gujarat Pogrom of 2002: Riots across the Indian state of Gujarat in the winter of 2002 in which thousands of Muslims were killed and hundreds of thousands displaced; Narendra Modi was chief minister of Gujarat at the time and played a key role encouraging the violence

HAF: Hindu American Foundation

Hindu YUVA: A U.S.-based Hindu Right student group, founded by the HSS

Hindutva: A transnational modern political ideology that advocates for Hindu ethnonationalist identity and goals

HMEC: Hindu Mandir Executives’ Conference; a VHPA project

HSC: Hindu Students Council, founded by the VHPA

HSS: Hindu Swayamsevak Sangh; the RSS overseas

Modi: Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi, RSS member and BJP politician

OFBJP: Overseas Friends of BJP; the US branch is a registered foreign agent

RSS: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh, an all-male paramilitary organization; central group of the Sangh Parivar

Sangh Parivar (or Sangh): Lit. “Family of the RSS”; a network of Hindu Right organizations across the globe.

VHP: Vishwa Hindu Parishad; within the Sangh’s religious wing.

VHPA: Vishwa Hindu Parishad of America; the VHP overseas

Notes

[1] Rebecca de Souza and Syed Ali Hussain, “‘Howdy Modi!’: Mediatization, Hindutva, and long distance ethnonationalism,” Journal of International and Intercultural Communication published online (2021): 4; also see the Getty Images photos collection of the event.

[2] de Souza and Hussain, “Howdy Modi!” 8.

[3] Amnesty International, “India 2020,” (2020); Human Rights Watch, “India: Events of 2021,” (2022); and United States Commission on International Religious Freedom, “Annual Report 2021,” (2021), 22–24.

[4] Sympathy for Hindutva within the Indian American diaspora is difficult to assess; the Hindu Right often promotes greater sympathy for its cause through soft Hindutva, a phenomenon discussed in “Cultivating Hindu Right Leaders on Campus” and “Intersectional Right-Wing Hate.”

[5] Savarkar’s book was republished in the late 1920s under the title by which it is more commonly known, Hindutva: Who is a Hindu?

[6] Bridge Initiative Team, Factsheet: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). (2021).

[7] Dhirendra K. Jha, “The Apostle of Hate: Historical Records Expose the Lie That Nathuram Godse Left the RSS,” The Caravan, January 1, 2020.

[8] Jaffrelot in Ajoy Ashirwad Mahaprashasta, “‘Not Hindu Nationalism, But Society That Has Changed’: Christophe Jaffrelot,” The Wire, January 25, 2020.

[9] Sanjoy Chakravorty, Devesh Kapur, and Nirvikar Singh, The Other One Percent: Indians in America (New York: Oxford University Press, 2017), chap. 2.

[10] Benedict Anderson, The Spectre of Comparisons: Nationalism, Southeast Asia, and the World (London: Verso Books, 1998).

[11] Prema A. Kurien, A Place at the Multicultural Table: The Development of an American Hinduism (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 3–4.

[12] Women are accommodated within the all-female Rashtra Sevika Samiti, which emphasizes gender-specific roles for women. Tanika Sarkar, “The Women of the Hindutva brigade,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 25, no. 4 (1993): 16–24.

[13] Madhav Sadashivrao Golwalkar, Bunch of Thoughts, (third edition available here), 264. “Ideological architect” is from Bridge Initiative Team, Factsheet: Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS).

[14] Christophe Jaffrelot and Ingrid Therwath, “The Global Sangh Parivar: A Study of Contemporary International Hinduism,” in Religious Internationals in the Modern World: Globalization and Faith Communities since 1750, ed. Abigail Green and Vincent Viaene (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 346–349.

[15] Anonymous scholar, “Transnational Hindutva Networks in United States,” testimony to the United States Commission on International Religious Freedom (2020).

[16] Ingrid Therwath, “Cyber-Hindutva: Hindu Nationalism, the Diaspora and the Web,” Social Science Information 51, no. 4 (2012): 568–572.

[17] Sangay K. Mishra, “Hindu Nationalism and Indian American Diasporic Mobilizations,” in New Perspectives on the Indian Diaspora. ed. Ruben Gowricharn (London: Routledge, 2021), 62; and Arvind Rajagopal, “Transnational networks and Hindu nationalism,” Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars 29, no. 3 (1997): 48.

[18] Christophe Jaffrelot and Ingrid Therwath, “The Sangh Parivar and the Hindu Diaspora in the West: What Kind of ‘Long-Distance Nationalism’?” International Political Sociology 1 (2007): 284–287.

[19] Jaffrelot and Therwath, “Sangh Parivar and the Hindu Diaspora in the West,” 285.

[20] Rajagopal, “Transnational Networks,” 45.

[21] Cited in Kurien, Place at the Multicultural Table, 145.

[22] Mentioned in Kurien, Place at the Multicultural Table, 145.

[23] Vijay Prashad, The Karma of Brown Folk (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000): 299–300.

[24] Sunita Viswanath, “What VHP America’s Invitation to a Hatemonger, Now Rescinded, Tells Us About Sangh Parivar,” The Wire, April 15, 2021; The Wire Staff, “Militant Hindutva Leader Yati Narsinghanand Arrested in 2 Cases, Sent to 14-Day Judicial Custody,” The Wire, January 17, 2022.

[25] Hindus for Human Rights, “Steps Away from U.S. Capitol, VHPA Holds Event on Kashmir with January 6th Rioter and Middle East Forum Leader,” July 29, 2021.

[26] Therwath, “Cyber-Hindutva,” 555.

[27] A 2020 article reported 220 HSS shakhas in the United States; Raqib Hameed Naik and Divya Trivedi, “Sangh Parivar’s US Funds Trail,” Frontline, July 16, 2021, 39.

[28] Chakravorty, Kapur, and Singh, The Other One Percent.

[29] Jaffrelot and Therwath, “Sangh Parivar and the Hindu Diaspora in the West,” 287.

[30] Therwath, “Cyber-Hindutva,” 563–564.

[31] Rashmee Kumar, “The Network of Hindu Nationalists Behind Modi's ‘Diaspora Diplomacy’ in the U.S.,” The Intercept, September 25, 2019. Also see Isaac Kent McQuistion, “Overseas Friends of the BJP, the Web, and the Power of the State in the Diaspora” (master’s thesis, University of Texas-Austin, 2017).

[32] Dilip Hiro, “How Tamashas Like Wembley are Part of Modi’s Strategy for the Next Election,” The Wire, November 21, 2015; “Spectacular images of PM’s ongoing US visit,” The Economic Times, September 30, 2014, image 19.

[33] Scroll staff, “Explainer: Why the ‘Overseas Friends of BJP’ has registered as a foreign agent in the US,” Scroll.in, September 14, 2020.

[34] Biju Mathew and Vijay Prashad, “The protean forms of Yankee Hindutva,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 23, no. 3 (2000): 529–530.

[35] 2002 report of IDRF’s alleged misuse of funds, “The Foreign Exchange of Hate: IDRF and the American Founding of Hindutva” and 2004 exposé on HSS and Sewa International in the United Kingdom, “In Bad Faith? British Charity and Hindu Extremism.”

[36] Kurien, Place at the Multicultural Table, 153.

[37] Jasa Macher, “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021: The Infrastructure of Hindutva Mobilizing” (May 2022), released via sacw.net: 20–21.

[38] Macher, “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021,” 20.

[39] Robert F. Worth, “The Billionaire Yogi Behind Modi’s Rise,” New York Times (July 26, 2018).

[40] Macher, “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021,” 48–49.

[41] Christophe Jaffrelot, Modi’s India: Hindu Nationalism and the Rise of Ethnic Democracy, trans. Cynthia Schoch (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2021), 16.

[42] Ashley Zhao, “Students Condemn Right-Wing Indian Activist’s Visit to Campus,” The Hoya, September 20, 2019.

[43] Prashad, Karma of Brown Folk, 314.

[44] See Kurien’s ethnographic work in Place at the Multicultural Table, chap. 10.

[45] For example, Mihir Meghani was a key leader in the HSC in the 1990s and, during that same decade, attended an RSS training camp (Coalition Against Genocide, “Affiliations of Faith: Joined at the Hip,” 4). Meghani wrote himself about his RSS experiences in “Tribal Tribulations,” Hinduism Today, April 1998.

[46] Vinayak Chaturvedi, “The Hindu Right and Attacks on Academic Freedom in the US,” The Nation, December 1, 2021.

[47] The manifesto is archived here, including a link to Mihir Meghani’s email address at the University of Michigan, where he was a student at the time.

[48] Prashad, Karma of Brown Folk, 299; Mathew and Prashad, “Protean Forms of Yankee Hindutva,” 527–528. Also see Biju Mathew, “Byte‐Sized Nationalism: Mapping the Hindu Right in the United States,” Rethinking Marxism 12, no. 3 (2000): 108–128.

[49] Naik and Trivedi, “Sangh Parivar’s US Funds Trail”; Macher, “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021.”

[50] As per publicly available 990 tax forms.

[51] Kurien, Place at the Multicultural Table, 12.

[52] This information is based on 990 tax forms, which gives limited insight into the precise sources of this funding.

[53] Kurien, Place at the Multicultural Table, 48–49; and Mathew and Prashad, “Protean Forms of Yankee Hindutva,” 521.

[54] Priyank Jaiswal, “Hindu Camp Changes Lives,” Hinduism Today, Winter 2002; and VHPA, “Hindu Heritage Day Celebrated on May 19th” (2017)

[55] Jaffrelot and Therwath, “Sangh Parivar and the Hindu Diaspora in the West,” 286, quoting the RSS mouthpiece Organiser from 1996. Also note the programming for parents by the Coalition of Hindus of North America.

[56] Christophe Jaffrelot, ed., Hindu Nationalism: A Reader (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2007), chap. 20; and Aria Thaker, “The Latest Skirmish in California’s Textbooks War Reveals the Mounting Influence of Hindutva in the United States,” The Caravan, February 6, 2018.

[57] Equality Labs, “Caste in the United States,” 2018. On the HSS operating as the Hindu Education Foundation, see Macher, “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021,” 24.

[58] Annie Correal, “Hindu Sect Is Accused of Using Forced Labor to Build N.J. Temple,” New York Times, May 11, 2021; Annie Correal, “Hindu Sect Accused of Using Forced Labor at More Temples Across U.S. ,” New York Times, November 10, 2021.

[59] Respectively, Sumitra Badrinathan, Devesh Kapur, Jonathan Kay, and Milan Vaishnav, “Social Realities of Indian Americans: Results From the 2020 Indian American Attitudes Survey,” Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, 2021; Equality Labs, “Caste in the United States.” Some U.S.-based Hindu Right groups promote, as part of their disinformation campaigns, that these two surveys conflict on the subject of caste (they do not, in point of fact).

[60] Jaffrelot, Modi’s India, 329–332.

[61] South Asia Scholar Activist Collective, “Select Timeline of Hindutva Harassment of Scholars,” 2021.

[62] Elizabeth Redden, “Donor With Opinions,” Inside Higher Ed, December 21, 2015.

[63] PEN America, “Threats to Participants in Hindu Nationalism Conference Risk Silencing Academic Freedom,” September 10, 2021; Hannah Ellis-Petersen, “Death Threats Sent to Participants of US Conference on Hindu Nationalism,” The Guardian, September 9, 2021.

[64] Jaffrelot, Modi’s India, 451; Mishra covers the involvement of diasporic groups in denying Modi a visa to visit the United States (Mishra, “Hindu Nationalism and Indian American Diasporic Mobilizations,” 67–68).

[65] On the 2014 Madison Square Garden event, see Vivian Lee, “At Madison Square Garden, Chants, Cheers and Roars for Modi,” New York Times, September 28, 2014. Note that the numbers, while impressive, are a small fraction of the Indian American diaspora.

[66] Rajagopal, “Transnational networks,” 49.

[67] Jaffrelot and Therwath, “Sangh Parivar and the Hindu Diaspora in the West,” 287.

[68] On Golwalkar’s admiration of Hitler, including the Nazi treatment of the Jews, see, for example, Madhav Sadashivrao Golwalkar, We or Our Nationhood Defined (Nagpur: Bharat Publications, 1939), 87–88; and Jaffrelot, ed., Hindu Nationalism, 98.

[69] Ties include prior affiliations with the James Madison Institute, Students for Liberty, and the Institute for Humane Studies. On Koch money and the US academy, see Ralph Wilson and Isaac Kamola, Free Speech and Koch Money: Manufacturing a Campus Culture War (London: Pluto Press, 2021).

[70] Jason Swindle, “An Interview with Drew Ferguson,” January 18, 2017, posted on Ferguson’s official congressional website.

[71] The event was held on March 28, 2022, called “Congressional Briefing - Biases Against Hindu Americans.”

[72] Macher, “Hindu Nationalist Influence in the United States, 2014-2021,” 36–38.

[73] Bill Chappell, “Alabama Will Now Allow Yoga In Its Public Schools (But Students Can’t Say ‘Namaste’),” NPR, May 21, 2021.

[74] For other comments on the relationship between racism in the US and Hindu nationalism, see, for example, Ishan Ashutosh, “The Transnational Routes of White and Hindu Nationalisms,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 45, no. 2 (2022): 319–339; Mathew and Prashad, “Protean Forms of Yankee Hindutva,” 523; Prashad, Karma of Brown Folk, 312.

[75] Pieter Friedrich, “All in the Family: The American Sangh’s Affair with Tulsi Gabbard,” The Caravan, August 1, 2019.

[76] Rozina Ali, “Hindus for Trump,” The New Yorker, October 31, 2016; Raza Rumi and Nihal Krishan, “Understanding the ‘Hindus for Trump’ Phenomenon,” The Wire, November 5, 2016.

[77] Mishra, “Hindu Nationalism and Indian American Diasporic Mobilizations,” 63–64.

[78] Mathew and Prashad, “Protean forms of Yankee Hindutva,” 521–522.